November 2024

Returning to Country

The plane touches down on Kalkadoon Country, known colonially as Mount Isa, and immediately something shifts inside me. The red earth stretches endlessly beneath leaden skies, a reminder of the deep history and continuing culture of the Kalkadoon people who have been custodians of this land for tens of thousands of years.

It's been ten years since my time running Corrective Services programs in the Lower Gulf, working through alcohol abuse and family violence. Those three years taught me the profound importance of connection to LORE, to community, to positive identity. But returning now to Kalkadoon Country, supporting Brodie's journey, I'm struck by how much I still have to learn.

Brodie picks me up from the airport, his energy infectious. We're here to work through his next phase of business development, supported by a Sport and Rec Queensland grant for three Camps on Country in 2025. The meeting with Sport and Rec feels like planting new seeds with strong roots. Paul Slater's presence - a respected Kalkadoon man who will mentor Brodie monthly - adds weight and wisdom to the conversation about mapping cultural protocols and partnerships.

Walking Brodie's World

As we drive through Kalkadoon Country, every second car holds a friendly face calling out to Brodie. Young people gravitate to his energy, hands reaching out for high fives, voices eager to share stories. These aren't superficial connections - they're threads in a web of trust he's woven through consistent presence and genuine care.

Wisdom from Uncle George

Sitting with Uncle George, a respected Kalkadoon elder, his words cut straight to the heart of what makes Brodie's work significant: "All the kids know Brodie and that's a big thing. He's only young and he can go a lot further." As a former Police Liaison Officer and custodian of cultural knowledge, Uncle George's validation carries special weight.

His insights about youth work come from decades of walking between worlds: "You can't just take people out bush for a week or two and expect they're going to change. These kids, a lot of kids will take years to change." He speaks about the importance of targeting the right young people, especially the leaders: "You've got to know which kids... especially around here, you've got a lot of leaders, a lot of kids that lead other kids. That's the kids you grab."

His reflection on how Kalkadoon Country has changed carries deep meaning: "When I was young here it was good here... Everyone got on. You could sleep outside, you could leave the doors open, everyone trusted anyone... Ever since the phones come in and all that, life's changed. And it's changed for the worst, not for the best."

The Men's Shed: Practical Wisdom

At the Men's Shed, Gary's practical wisdom emerges through action rather than words. As Men's Shed Coordinator for Nook and Tardy, ourari, our children and family centre, he has created more than just a workspace - it's a sanctuary where healing happens through doing.

The shed hums with possibility. "We just basically do woodwork," Gary says with characteristic understatement, before revealing the deeper purpose. They started with pallet work, creating beds and medicine cabinets for the elderly "where they can lock it up." Then came the bike program, breathing new life into cycles salvaged from Townsville's floods. "That container at the front, that was full of bikes... Took us to get rid of all them bikes, all the kids that are walking."

But it's more than just making things. The shed serves as a crucial transition point for men seeking new directions. "We get the men from CASH, that's our diversion recovery centre. Some come out of the jail, come straight into that system," Gary explains. These men find their way to the shed, where they're welcomed without judgment into what Gary calls "a real honour circle."The innovation in Gary's approach lies in seeing possibilities where others might see waste. The wire work program emerged from this vision - "because you can find work wire anywhere in the community man you know." These creations, from totems to fencing, offer pathways to income for men rebuilding their lives.

Perhaps the shed's most powerful initiative was the suicide prevention march that began six years ago. "We was the only Indigenous men in Australia to do a suicide march," Gary recalls with quiet pride. The impact rippled across the country, inspiring similar movements. In Mount Luby, where they lost 22 people in one month, a men's group grew from three to 250 members after following the shed's example.

The space serves multiple purposes - a refuge ("I'd rather you run here than stay there and bash them"), a learning center (teaching welding and trades), and a connection point where men find purpose through practical work. Success stories emerge naturally: "Out of the 10 years of me, I think two of them were in the mines. One's got a trade as a boilermaker, now he's flying in and flying out from Townsville."

When we discuss the create bed project, Gary immediately sees its potential through the lens of community need. "We've got a lot of homeless people down the river and that's all they is mattresses... diseases mattress material you know the scabies you know all the bed sores and everything." He envisions not just providing beds but teaching people to make them - "give me a hand, make it, you know, and they can take the skill to make it."

The shed's latest project, the Red Benches initiative, exemplifies their approach to complex community issues. Working with young people from T2S and Flexi school, they're creating visible symbols of domestic violence awareness while teaching practical skills. "We made them and the women painted them and they did the artwork on them... it was a joint venture with the men, you know, for DV."

In Gary's world, every project serves multiple purposes - teaching skills, building confidence, creating practical solutions, and weaving stronger community connections. As he says, "Sometimes you don't have to do the cultural stuff. You can just sit down and yarn and listen, really." It's in this space of doing and being together that real change takes root.This practical wisdom offers a powerful model for community development - one where healing happens through purposeful action, where skills transfer naturally through shared work, and where every project strengthens the web of community connection.

Seeds of Change: The Create Bed Adventure

What began as disappointment at Bunnings - no crates available for our bed project - transformed into a journey of community connection. Gary at the Men's Shed pointed us toward Good Shepherd Church, where an unexpected reunion with Aunty Dolly. A decade dissolves in an instant. Aunty Dolly, who once helped countless community members return to Country for sorry business and health-related trips, opens the door. Her initial uncertainty breaks into recognition, and suddenly we're connected across time. These are the moments that remind me of the deep relationships that hold communities together.led to our first breakthrough. Her immediate response of "just go for it" when hearing about the create bed idea opened the first door.

The next day, after checking with Father Mick who directed us to Coles, we found ourselves negotiating for crates - initially just borrowing them with a promise to return. In true community spirit, we ended up giving back more than we borrowed, turning a temporary loan into a gift that kept giving.

The real magic happened in the building. With Mark, the experience transcended simple furniture construction. Here was a man who'd been sleeping on a bed frame with just a piece of wood the night before. Working alongside Brodie and other men who trust and support him, we created more than just a bed - we built connection, dignity, and possibility. Mark's quiet pride in having a create bed "for as long as he wants" spoke volumes about the project's deeper impact.

The energy continued in Pioneer, where we turned bed-building into a family event. A 13-year-old lad joined the assembly team while family members kept time, turning work into play. Watching the bed rise on the balcony, becoming a play space for all the kids, showed how these simple creations could serve multiple purposes - practical solution, community activity, and source of joy.

These moments of collaborative creation proved what Gary and Uncle George had been saying about real community work. It wasn't about formal programs or bureaucratic processes - it was about practical action that brings people together, solving immediate needs while building relationships and skills.

The create bed journey became a perfect example of how solutions emerge through community connection - from Gary's guidance to Aunty Dolly's blessing, from borrowed crates to shared labor, from addressing immediate needs to creating spaces for play and dignity. Each bed built strengthened the web of relationships that make community change possible.

Learning from Doomadgee Visitors

At the river bed, we meet a couple from Doomadgee. Their quiet presence carries decades of wisdom. Testing the create bed, their responses are measured but meaningful. "Nothing like this," they say, comparing it to the springy mattresses available in their community for $180. Their approval is simple but profound: "The best."

Their guidance about community engagement teaches me about proper protocols. When I ask about visiting Doomadgee, their answer is clear: "You can ask the Council, and that'll help you and then talk to the community and all that." This is the way - no shortcuts, no assumptions, respect for proper channels and community leadership.

Aunty Joan's Sacred Knowledge

Sitting with Aunty Joan becomes one of the week's most profound moments. Her insistence on not being recorded speaks to the sanctity of story. Instead, she shares her carefully preserved workbooks, self-taught writing alongside precious photos that document a life lived close to country.

She shows us images that tell the story of colonisation - how it tried to define what they could do, how life was supposed to work, how it attempted to limit their way of living on the land. Her stories of driving sheep at 14, her working history, her ability to carve a beast, and her deep connection to cooking on country with family aren't just memories - they're vital knowledge at risk of being lost.

Her concern about cultural disconnection cuts deep: "A young person would not be able to pick out the bush that you smoke to help a mother's lactation after pregnancy." She sees how the modern world is disconnecting young people from the LORE that for so many years helped them understand life at a different level, supported a community of people helping each other and caring for the land.

Brodie's Growing Impact

Throughout the week, we witness Brodie's natural leadership in action. At the Flexi school on Kalkadoon Country, young people flock to him, eager for connection. The teachers implore him to come more often, to create programs that mentor youth, connect them to the gym, and then guide them on country.

Uncle George's words about Brodie's potential resonate: "He's on the right track. But he's trying to do it himself too, like I do. And that's the thing. When you're trying to do things by yourself, it's very hard to change. If you've got another four Brodies or four of me or something, it's going to make things a lot easier."

The Complex Reality

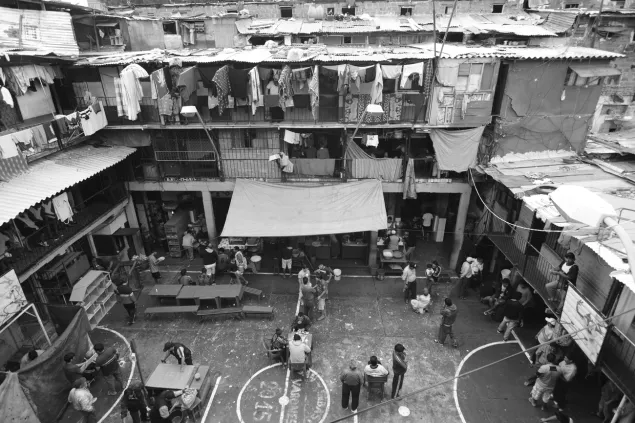

Kalkadoon Country holds its contradictions openly. The billions generated by the mines cast long shadows over community poverty. At the river bed, people sleep on old mattresses and work through their trauma with wine bags and cartons of beer. Young people walk streets instead of attending school.

Yet hope grows in unexpected places - in the Men's Shed's quiet work, in Aunty Joan's careful preservation of stories, in Brodie's dedicated presence with youth. As Uncle George says, "You can stop it, I tell you right now, if you get a group of good people together."

A Personal Reflection

As I prepare to leave Kalkadoon Country, I'm humbled by how much I still have to learn. Most of the time when I talk about community work, I hear white people telling me what it's like in community, how I should act, what happened to them and what I need to do. I still don't know how to take this, but I stay quiet and continue to learn on country from elders, Traditional Owners and community.

I feel privileged that people have opened their worlds to me across many traditional lands - from Bwgcolman (Palm Island, where many tribal groups were forcibly relocated, with Manbarra people as traditional owners), to Minjerribah (Stradbroke Island, home of the Quandamooka people), to Mparntwe (Alice Springs, home of the Arrernte people), and here on Kalkadoon Country. In each place, people have shown me protocols, walked me through ceremony and spent deep time talking through ideas and opportunities.

The contrast here on Kalkadoon Country is stark - between the billions of dollars generated from mining on traditional lands and the poverty visible in parts of the community. At the river bed, people sleep on old mattresses and work through their trauma. Young people walk the streets rather than being at school. The privileged community looks down on issues that are in their face, not sure how to take action.

Through A Curious Tractor, Nic and I remain deeply curious to know more while standing with community in developing, trialing and testing solutions. There will be times we get it wrong. People might growl at us. Many will disagree. But what we have are strong local people leading us in the right ways, building our understanding.

I don't seek acceptance - that's not what this work is about. I want to offer my skills, do things with community, help when asked, and work through things I don't know. I want to walk alongside people when welcome and try to tell this story of hope, resilience and connection to Mother Earth that too many people have lost.

I believe Indigenous thinking offers a way through many of the issues we face in this generation. When Aunty Joan speaks of traditional medicines, when Uncle George talks about community responsibility, when the couple from Doomadgee quietly demonstrate proper protocols - these are not just stories or rules, they're pathways to healing that have sustained people for tens of thousands of years.

I want to share that thinking in the hope some will listen and reconnect with nature in the way that First Nations peoples have done since time immemorial. As Uncle George says, "If you speak from the heart and you tell, and you say the right things and you speak the truth, people listen."

Standing here on Kalkadoon Country, watching Brodie work with young people, seeing the elders share their wisdom, witnessing the quiet strength of community connections, I understand more deeply than ever that our role is to listen first, to learn always, and to walk alongside when invited. The solutions aren't in grand gestures or outside expertise - they're in the patient work of supporting community-led change, one relationship at a time.

In the end, it's about understanding that every traditional Country holds its own wisdom, its own protocols, its own ways of healing. Our job isn't to bring solutions, but to support the knowledge and leadership that already exists in community, while remaining humble enough to keep learning, growing, and changing ourselves.

As I board the plane to leave, I carry these lessons with me, knowing they'll continue to teach long after this visit ends. The privilege of being welcomed into these spaces comes with responsibility - to listen well, to support wisely, and to share stories in ways that honour their depth and complexity.

.svg)